Gabby Woehr

“You never know what it is going to be, the thing that someone will connect with.”

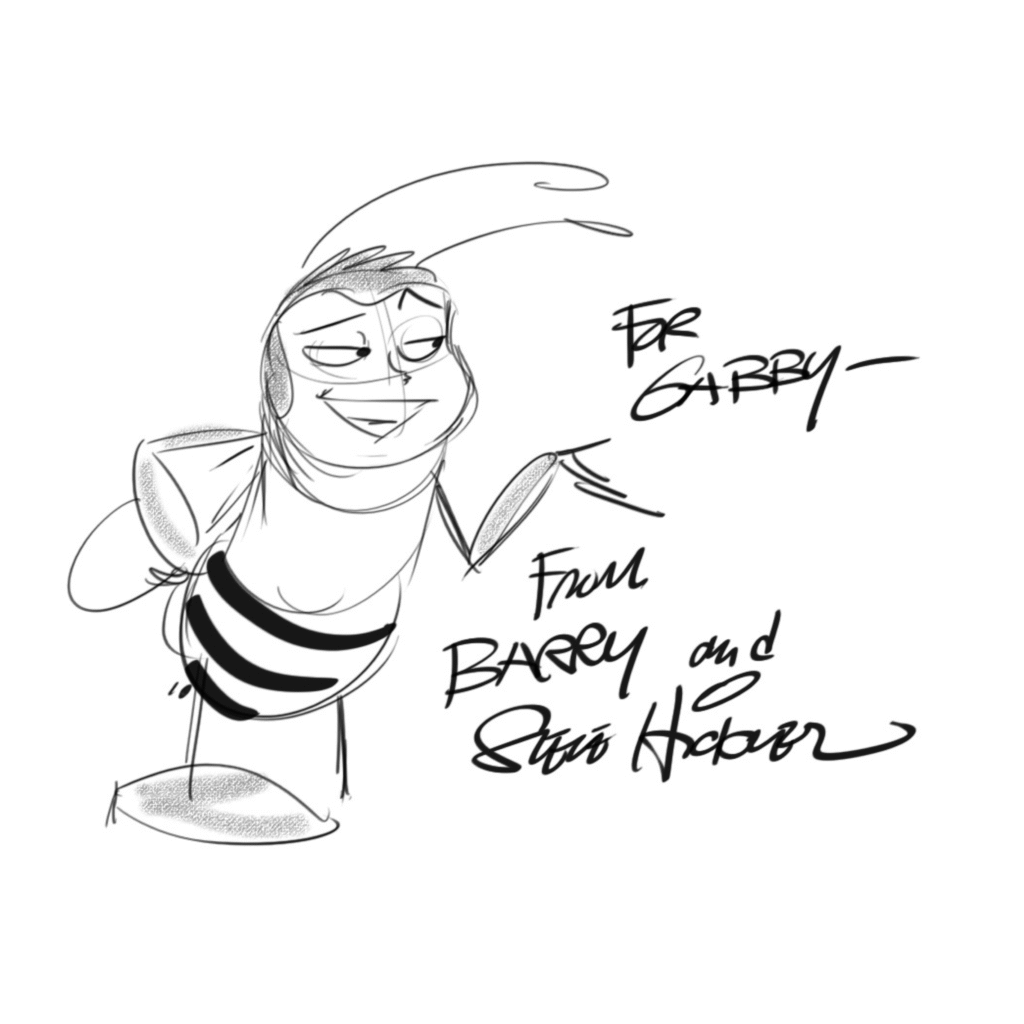

— Steve Hickner

The audience of a film acts as the jury before which a trial is unfolding. Its members are inclined to make judgments as each scene unfolds, preparing a final verdict that can be funnelled into a score on the Tomatometer. The theater is a courtroom where characters, plotlines, and camera angles can either be exonerated or sent to the gallows. When an audience leaves a theater, they have participated in a moment of unique justice, either rewarding or punishing the product of someone else’s work.

Films in the 21st century often struggle to meet the expectations of artistry set by famous works — notably, Citizen Kane (1941) and The Godfather (1972) have cast shadows over future filmmaking with their accomplishments. As widely agreed, part of their greatness has been their ability to be viewed differently by each audience member. Because animated films are often viewed superficially, there are few that measure up to these standards of interpretation. One such film is the indomitable Bee Movie, a 90-minute feature ripe with analytical promise. The 2007 animated film has cemented itself as a historically significant piece of art, one whose insights speak to the aspects of life for which we constantly seek explanation: love, purpose, and belonging.

Bee Movie’s most important takeaway can be debated at length, as the movie speaks to class divides, work culture, and environmentalism, among other issues. One walks away from the film with a renewed sense of passion for fellow creatures, most particularly for the honey-making, human-fearing bee. The movie follows Barry B. Benson in his journey to find fulfillment within his hive. Appalled at the reality of lifelong work, Barry explores the human world, where he builds unexpected relationships. These bonds facilitate his opposition to commercialized honey, culminating in a lawsuit that returns honey’s rightful ownership to the bees.

The complicated nature of the film’s plot yields its many possible interpretations. Perhaps it is a commentary on human work culture — one feels that the film is speaking to them when it proclaims: “You… have worked your whole life to get to the point where you can work for your whole life.” The film speaks to the purpose of work in bees’ lives, and similarly could be applied to humans. Steve Hickner, the co-director, also a veteran animator and currently a professor at Ringling College of Art and Design, gave his thoughts on work, saying it “gives meaning to” life. Thus, his creation could be a manifestation of this principle; the bees find fulfillment in volition, as do we.

Contrastingly, it could be a statement about love — Barry, a bee, and Vanessa, a human, build a friendship that functions in spite of species differences. It could be urging readers to form unlikely relationships, building bridges across oceans of apparent differences. As Hickner says, Barry and Vanessa’s bond is “absurd”, but it sustains both characters as the movie progresses. Any viewer should feel compelled to walk out of the theater and into a friend’s arms.

According to Hickner, the real intended message of Bee Movie is simple; there isn’t one. In his words, “It was only meant to be funny. Anything else you get is good, but it better be funny first and foremost.” In a film so saturated with potential meaning, a guiding principle of humor seems counterintuitive. However, its humor provides the foundation for unique interpretation. Because there was no intentional messaging, the movie acts as an almost reflective blank slate; it is a mirror in which an audience can see their lives, opinions, victories, and losses.

Bee Movie’s lack of focus creates an ultimately more profound phenomenon: an ability to be applied to a variety of societal topics. Whereas films that try to comment on a specific issue often miss the mark, Bee Movie’s genius is in its generality. It can be a critique on class divides, with humans representing the bourgeoisie while bees act as the proletariat. It can also be an environmental petition, as Hickner mentioned “Colony Collapse Disorder” as a potential problem addressed in the film. The film speaks to the importance of bees in ecosystems, incidentally but importantly. It can be a retelling of landmark court cases, a modern-day Romeo and Juliet, or an allegory of the American Dream. Like the audience of an artwork, Barry enters a courtroom with unique traits that compel him to fight for his convictions. His own act of judgment sets an example for viewers, contributing to the cornucopious interpretations of the movie. Anything a viewer sees in the movie is valid because the moral of the story remains undefined.

The diversity of potential interpretations represents a broader truth about storytelling; artistic interpretation belongs to the audience of a text. Authorial intention matters during the creative process. However, once a work reaches viewers, it belongs to them. Books belong to their readers, songs to their listeners, and films to the high schoolers that agonize over them for Creative Writing assignments. Creators are not the rulers of their creations. If an audience sees value in a work that its author did not, the value is still there. It cannot be revoked because it was unintended.

From the perspective of the creator, Hickner agrees that “we all think about things and maybe they’re there, and we don’t even realize it when we’re making it.” Authorial intention, as Hickner says, is incomplete because subliminal morals can permeate a story. These morals are often internalized by audiences, regardless of how unexpected they may be. “You never know what it is going to be, the thing that someone will connect with.” In other words, a viewer can glean many things from a film, which is the very principle that makes cinematic analysis flexible. If many interpretations are possible, there is not solely one that is correct. The variety in conclusions does not equate to invalidity. Put simply, interpretations are as diverse as a text’s audience because each person has a unique perspective.

There is a certain dissonance that exists between creators and viewers, one that makes the messaging of a film subjective. If a director intends for their movie to speak on societal issues in a profound way, but society rejects it, it has not accomplished its purpose. In contrast, if a director creates a film with no desired message, and it is received profoundly, it has achieved something meaningful. Movies carve nests in our hearts and perch in them, allowing us to interpret them uniquely.

While audiences act as juries that decide movies’ fates, there are key differences in how one enters a theater and a courtroom. In a courtroom, one must be impartial and fact-driven. In a theater, it is an audience member’s duty to enter with their biases, beliefs, and emotions at the forefront of their mind. It is from these preconceptions that interpretations are built — interpretations that are as diverse as those that create them.

Gabby Woehr is an 18-year-old writer. She has participated in the Adroit Journal Mentorship and her writing has been exhibited and honored by the Scholastic Writing Awards. Her work includes prose, poetry, and creative nonfiction. She lives in Indianapolis with her family and extensive pantry.

Featured photo: Bee Movie (2007) theatrical release poster from IMDB; in-text illustration provided by Gabby Woehr