Marie Cloutier

One sunny Wednesday in April 2022, I wandered into a stationery store in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles. I tagged along on my husband’s conference trip and after a museum visit hoped to find some fun Hello Kitty souvenirs among its shops and stalls. I’ve been a Hello Kitty collector since girlhood and smiled to come across a pink notebook with a kimono-clad cat on the cover next to a stack of pink pens. But I had also been grieving my ex-lover’s death for two months and spending much of the time alone, sightseeing through a haze of tears. I purchased a notebook and a pen and thought how I might fill the book.

I met my ex in an online chatroom in 1991, I an 18-year-old college student and he a 66-year-old philosophy professor far away. Online chatting quickly became daily phone calls. I was enthralled with his humor and smarts; I was dizzy from his attention, dazzled when he said he was lucky to have me in his life. We’d met twice and he was my first lover. By the time it ended, he’d taught me I had value and deserved to be loved. It was only later that I discovered the existence of his wife and family. This relationship was my secret; almost no one in my 2022 life knew anything about it. To most, I was happily married with a normal life. When he died I collapsed along fault lines I’d believed would never shift. Early in my solitary mourning, I’d learned the term “disenfranchised grief,” private grief connected to relationships deemed socially unacceptable or felt to be inconsequential. Sometimes I wasn’t sure I even deserved to grieve this man and our long-ago love affair. Talking to anyone felt impossible.

When I returned to the hotel room with my new notebook and pen, I wrote out an intimate scene taking place midway through our relationship. I had tried to write this story before; this time, like every time, fictionalizing it seemed like the safest approach. I used made-up characters and a different setting. I aged myself up and him down. I had never heard anyone tell a story like mine and I thought no one would believe me. But even early into a grief that would be at the center of my life for months to come, I knew I’d need to write about it to move on. When I sat down that April afternoon I still believed that fiction would allow me to process my feelings and keep the true story hidden.

I exhaled and tried to get comfortable on the hotel bed. I fidgeted and tried to find the right footing. I wrote what details I could, then put on a movie and ordered a cheeseburger. I tried again later, and again the attempt fell flat, alienated as I was from my own story. The disguises felt like a surrender to shame.

The only thing that would work was the truth.

Months later, I tried again with a copy of Maggie Smith’s Keep Moving: The Journal on my desk. I did one prompt-based exercise per day. I wrote as little or as much as I felt like. I put it aside when it felt like too much. When I filled her book I started one of my own.

Because it was telling the truth—unvarnished, uncrafted, first in Maggie’s book and later in a little blue notebook I showed to no one—that helped me rediscover my purpose. I have always been a writer—poems, blog posts, and all that dead-end fiction—but as I filled those books I began to think of myself and my art differently.

I read Annie Ernaux’s A Girl’s Story, captivated by her use of split persona—the young woman of the story and the mature woman writing it. In the privacy of my notebooks I started to experiment with voice. When I returned to the intimate scene I’d written as fiction, the “she” was I. The switch opened a whole new landscape of perspective. The Marie at 18 was a different person than the Marie writing at 51; detaching myself from her, I could explore her as her own character. I found I was kinder to her than I had been to myself. I judged her less. I focused on the details surrounding her—what she saw, how the rain felt on her shoes the day she met him in person for the first time, the meal they shared in that hotel room. I could separate myself as the writer from the girl I was writing about and a different sound emerged. I continued the exercise in longer sections. When I found that I couldn’t sustain the tone and had to revise, it didn’t matter because the door had been opened. I could use what I generated and I had tools to generate more, sneaking into dark corners of memory as both myself and someone different. In the meantime, I participated in a weekly writing group with opportunities for random prompts and nonjudgmental sharing. I learned that my creativity was always at my disposal and I could make whatever I wanted on the page. I started taking classes and continued to challenge myself with form. I wrote and started to publish flash and poetry, including a poem about Hello Kitty. I reused memories and ideas from one piece to the next, writing a poem and a flash piece about the same thing from different angles, finding nuance along the way. There was so much I had to say. As I gained traction and built momentum, my work and identity as an artist started to melt that old isolation away.

In exploring form and voice, and acclimating myself to sharing, I learned that sometimes what you believe you have to hide is the superpower that connects you to your creativity and helps you make the art you were always meant to do.

Marie Cloutier (she/her) is a writer and a poet based in the New York City area, where she also studies piano and Yiddish. Her work has appeared in Dorothy Parker’s Ashes, HerStry, Corvus Review, Bare Back Magazine, Neologism Poetry Journal, Haiku Universe and elsewhere. She is currently at work on a memoir about disenfranchised grief. Her website is www.mariecloutier.com and you can find her on Instagram @bostonbibliophile2.

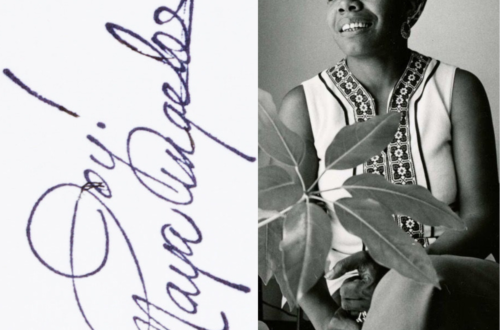

Featured photo by RDNE Stock project (Pexels)