Amlanjyoti Goswami

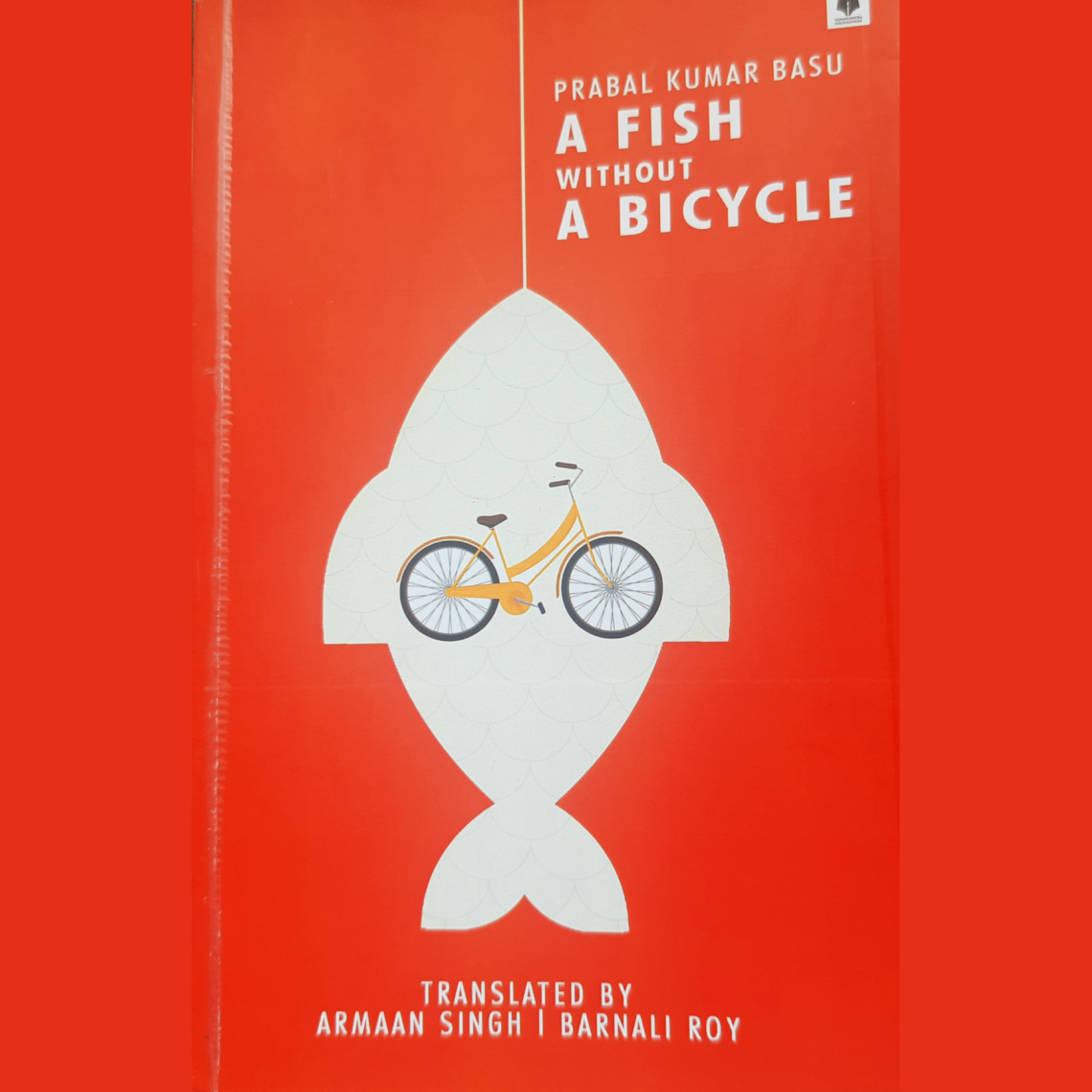

Prabal Kumar Basu’s book of poetry, A Fish without a Bicycle (translated by Armaan Singh and Barnali Roy, Yapanchitra Foundation), is a book of whimsical fancy, where surreal realities intersperse with romantic yearning. The result is neither a fantasy nor a feeling of complete loss. It is somewhere in-between, perhaps like middle class and middle age. The title of the book is derived from the celebrated feminist phrase, “a woman without a man is a fish without a bicycle” (Irina Dunn, 1970). In the poem ‘For Amulya’s Dreams,’ the poet recalls Amulya who “desired to be a duck and float on the water/ but couldn’t gather the courage/ and a feminine voice could be heard calling out,/ Sir! Sir! From behind.”

The country is frequently lost in the book and this search for a missing country inspires poetry. In “Gone Missing,” the poet asks: “What is amiss? Something is missing/ This land, India, my country has gone missing.” When the feeling of loss is not overcome, there is a feeling of not-quite-being-there. “Success lives next door/ I see him cross the road daily,” he grimly discovers in the poem, ‘Success and I.’ Sometimes the gaze is directed at oneself. In ‘Be with Me,’ the poet confesses, “I’m fast fading away/ like a cigarette tapering off/ as it passes hands on a winter night.” This is the good ol’ romantic reminiscing with nostalgia, and what greater loss can there be than the loss of one’s own self.

Yet, this is where the fun begins, when the poet lets go of the self and conjoins strange fantasies of whimsy. In ‘Che’, he meets a very ordinary Che (assumedly Guevera, though not mentioned) who “keeps living somewhere/ learning to be a conformist, perpetually adapting/ as is the normal evolution of any Che.” Che is joined by others of similar ilk, such as Fidel, who “wakes up early in the morning” and “he has this habit of going for a morning walk/ just like me.” Lenin follows, and then comes the retinue — Shakespeare, Jibanananda and finally God. All this happens in the poem, ‘A Day in the Mundane Life,’ which seems anything but mundane. All the high and mighty reduced to ordinary roles, like everyman. Such are the subtle claims of modernity!

In Basu’s poetry, when a cat sees its reflection on the water, it looks like a tiger, and they square off in a battle of wills. A twentieth floor is a dizzying height but not of much use because terra firma is still so far away. Inherited bylanes can never lead to a highway. This is a poetry of changing landscapes, as village turns into town, and town becomes city.

The best poem in this book is ‘The Story of the River’ where “coming out of a nursing home in the darkness of night/ a river went right inside a tree.” This event goes unnoticed for a while, till the fated moment when the tree has to be cut down to expand a road. Inspite of warnings from those who knew what trouble would befall, workers cut down the “river tree,” only for the surging waters to wash away villages and towns on the way. Ecology, yes, but nicely tucked in with a little folklore, which too is a disappearing reality in a changing city.

Amlanjyoti Goswami has written two widely reviewed books of poetry, River Wedding and Vital Signs, both published by Poetrywala. River Wedding was shortlisted for the Sahitya Akademi award. Published in journals and anthologies across the world, including Poetry, The Poetry Review, Penguin Vintage, Rattle and Sahitya Akademi, he is also a Best of the Net and Pushcart nominee. His work has appeared on street walls of Christchurch, buses in Philadelphia, exhibitions in Johannesburg and an e-gallery in Brighton. He has read at various places, including Delhi, Mumbai, New York, Chandigarh, Boston and Bangalore. He grew up in Guwahati and lives in Delhi.