Anita Nahal

Genre: Poetry

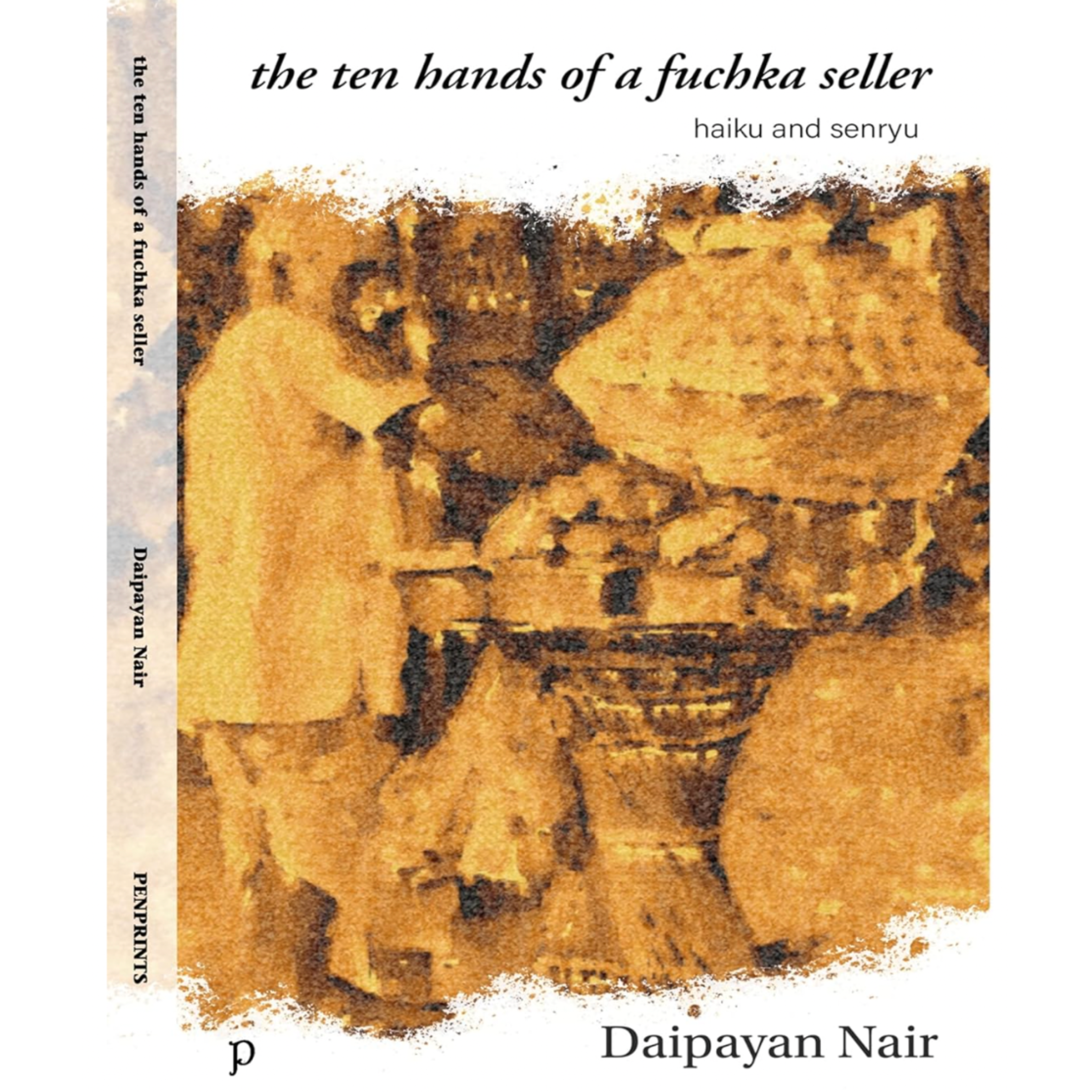

Publisher: Penprints (2024); ISBN-10 8197403627

Price: ₹300 / $35

Pages: 79

There is something earthy and grounded about haikuist Daipayan Nair’s 2024 collection, the ten hands of a fuchka seller (haiku and senryu). At the onset, let me identify that fuchka is a savory street food in India. Also, let me say a few words about the winsome beauty of the jacket with its golden hues splintering at the edges. It gives the impression that the painting is joyfully collapsing into fine pixie dust. And that, in a nutshell, sums up this endearing collection—heart touching and resplendent!

For a diasporic writer like me, this charming and poignant haiku collection grants a welcome nostalgia about India, especially Kolkata, and also lets me breathe in fully the universality of a globally connected world. As Santōka Taneda, Japanese author and haiku poet, expressed quite rightly, “Haiku is not a shriek, a howl, a sigh, or a yawn; rather, it is the deep breath of life.” Most poems in Nair’s collection feel like “… deep breaths of life.” In essence, even though I haven’t been to Kolkata, I can envisage, almost like in a mind map, Daipayan’s haiku. If I wish, I can inhale a long aura of these poems, leaving indelible marks of Bengali culture, arts, and locale in my mind and heart. They remind me of Satyajit Ray films with actresses like Sharmila Tagore and Aparna Sen walking rooms and corridors, involved in daily work and rituals. Some of the poems are sensual: “red blouse / a safety pin between / her lips” (p. 45); and some are frugal though also ocular like most others: “after a bath / mustard oil trickles / down grandpa’s ear” (p. 70). Some lay in the private setting of a home: “agaru oil / ma sprinkles her hymn / over the marigolds” (p. 44); and some in public environs: “raining petals / the street sweeper stretches / her spine” (p. 37).

Daipayan’s haiku leaves an ache, a haunting desire that seems somehow to be soothed by the meditatively placed words on the thoughtfully crafted pages. Some black-and-white pictures are also interspersed within the pages, which makes the book visually appealing at a visceral level.

Folks might ask which poem was my favorite. It’s tough to say as creativity is personal and subjective. For me, it’s the overall feeling that a collection cumulatively brings and not about liking or disliking some poems in a book. Nair’s poems certainly feel inviting, thought-provoking, and also very political. As we know, the personal becomes political when thoughts are revealed in words. Nair employs quiet yet emphatic haiku vignettes to talk about class difference: “returning home / on a hand-pulled rickshaw / school song” (p. 17); gender roles: “shaking a jar / of roasted raw mangoes / grandma’s noon” (p. 14), age: “park sunset / an old man’s laughter holds / his wife’s hand” (p. 35); and cultural issues (references to Kolkata streets, Kolkata biryani, the Ganges, Sadhus, etc).

The lexical choices we make in our writings, or verbal expressions, convey a lot about our own background and origin. Besides being a poet, I’m a historian by profession and seeking the subjective rather than the objective in speech and writing reveals a lot to me about the author’s frame of reference and thought process. Rock artist Michelle Malone said, “Art is so subjective—it means something different to every person. The important thing for it to do is to touch on the senses and emotions.” Ultimately, as historian E.H. Carr astutely explained in his supremely well-recognized book, (What is History?), there is no objectivity in history (or in life I would say), and as Einstein’s relativity showed, space-time can be pulled, curved, or stretched. And so, Nair’s haiku are a conglomerate of his vision and interpretations of life in his city and his world in myriad and relative forms.

Many pages in the book remind me of an ink pot that someone walking by in a dhoti and kurta—or a Bengali sari with house keys tied to the end of the pallu draped over the shoulder—accidentally knocks over. That act of mistakenly hitting the ink pot and spilling its remarkable cobalt ink has immense relevance indeed, for it is followed by hushed blue footsteps walking over the hungry paper in whispers, revealing dreams and reality in tiny three-line golden nuggets. For a prose-poetry writer such as myself, Daipayan’s book makes me fall in love with the form for its refined simplicity and elegance.

On each of the book’s 79 pages, there is a symbiotic relationship between the palpable and the make-believe world. It’s not that the immense high level of creativity that Daipayan seeps into his haiku-senryu is surreal or that it does not exist in our normality—it does. However, a keen poet-artist’s eye is required, which the author has in abundance. As Robert Hass, American Poet Laureate (1941-1995), said, “Haiku is an art that seems dedicated to making people pay attention to the preciousness and particularity of every moment of existence.” Daipayan has certainly achieved this in this precious collection. Here are some examples with a short interpretation for each as per my understanding. As mentioned above about subjectivity, the reader and receiver too are as such.

* graffiti art / an old beggar pees / on revolution (p. 13) — public, Kolkatian or anywhere in India, and local or global in reference to “revolution”.

* between / the city buses / her face (p. 15) — public, sensual, real or fathomed, dreamt.

* scattered fishbones / a young waiter gathers / his thoughts (p. 21) — public, class, food.

* Kolkata biryani / she leaves her memory / on my tongue (p. 42) — Kolkatian, sensual, personal, food.

* false tooth / grandma grabs a fistful / of puffed rice (p. 65) — personal, home, food.

* bhog thali / the priest makes space / for his last demand (p. 65) — public, private, spiritual.

* behind / the bookshelf / two lizards (p. 78) — universal, public, real or fathomed, dreamt.

The above few examples interspersed in my review don’t do justice to the richness of this book. One has to savor it over and over again.

the ten hands of a fuchka seller can be purchased here.

Anita Nahal, Ph.D., is a two-time Pushcart Prize-nominated (22, 23) Indian American author-academic. She was also a finalist for the Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize in 2023. Anita has four poetry collections, four books for children, one novel, and five edited poetry anthologies published. Her third book of poetry, What’s wrong with us Kali women? is prescribed as mandatory reading at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. She teaches at the University of the District of Columbia, Washington DC. www.anitanahal.com