Ravibala Shenoy

Paimaam retired from a long service in a government department fifteen years ago, but still liked to be in the company of high officials. It was not that these officials did any special favors for Paimaam: in fact, he didn’t say much in their presence, he merely nodded his head to show accord with whatever the high official happened to say.

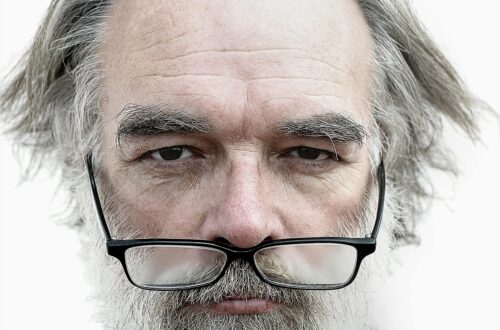

Paimaam was tall and lanky, bespectacled, quick of movement, with a brow that wrinkled in sympathy with the problems of the people talking to him. He was no Lothario, but he would slap his forehead and shake his head in despair to show sympathy for the chief’s wife’s glaucoma or the director’s mother’s sciatica, and he inveigled his way into the homes and hearts of the high ups with small presents such as bags of fragrant jasmine and bread fruit from his garden, or by planting a palm sapling in the garden of the newly retired director’s house.

Except for this one weakness, Paimaam was a simple man. His greatest pleasure was eating sliced packaged bread with butter and drinking a cup of hot tea. His wife whom everyone called Mami, was patient and submissive, an unworldly woman, but she lit up his household. He slept soundly every night and had regular bowel movements. What more could a man of his age ask for?

Paimaam often came to Delhi alone, but on this occasion, he brought his wife along. To show her the sights, he took her to the Khadi Bhavan Emporium near Connaught Circle. There they purchased a baby quilt for Wagh’s new grandchild.

Mami was fascinated by the wide variety of items displayed at the Khadi Bhavan: the bust of Mahatma Gandhi, handicrafts, garments made of homespun khadi and khadi silk. Mami did not want to buy anything for herself, but she couldn’t bring herself to leave the store. Paimaam, though an inveterate Khadi user, was bored. But he did not wish to displease his wife, so as a compromise he suggested that she should stay on and see all parts of the store to her heart’s content, while he made his usual social calls on the Waghs and other high ups of his acquaintance. Mami agreed.

While she was still feasting her eyes on every part of the store, one of the shop assistants approached her and said it was 12:30, time for the store to close for lunch. Mami was disconcerted to see that she was the only customer there. The shop assistant graciously told her that she could return at 3:00 p.m. when the store reopened.

Mami did not know what to do. She had brought no money or a phone because she was with her husband. She stood on the pavement outside the store and waited for Paimaam.

At one o’clock there was still no sign of Paimaam. Her eyes ached looking out for him, her legs ached, and hunger gnawed at her insides. There was no point in torturing herself, so she plumped down on the bare ground in her freshly ironed cream-colored cotton saree. Passersby cast curious glances at her, wondering why a respectable looking matron was sitting on the pavement. Mami feared the worst: Why does he frisk like a calf in springtime around those high ups? At his age! For what purpose? Does he think hobnobbing with the powerful makes him powerful? What if he were struck by a bus or a car in this foreign city where she knew no one?

***

Meanwhile Paimaam rang the bell of the Waghs’ second floor apartment. Wagh was the head of an important government department. Mr. Wagh’s daughter had just had a baby girl.

“Paimaam, what a lovely surprise!” the young mother said, opening the door to the visitor.

Paimaam entered the dining room where Mrs. Wagh and her octogenarian mother-in-law sat. He beamed at the infant who burbled contentedly in her crib. “A beauty,” he commented. “Like a princess.” His eyes were wide with emotion behind his thick glasses, “May you have a long, happy life!” He placed the wrapped present into the crib.

“You are so thoughtful, Paimaam,” the young mother bent down to touch Paimaam’s feet.

“Paimaam,” Mrs. Wagh urged, after Paimaam seated himself at the table, “Please have some tea. Will you stay for lunch?”

Paimaam declined the invitation.

“Well then, you will have to excuse me, because I must attend a building residents’ meeting. It shouldn’t take more than half an hour. My husband will be home soon.” Mrs. Wagh said, before sailing out of the front door.

Paimaam looked at the baby who gurgled at him.

“She likes you!” the daughter said. “Would you like to hold her?”

Paimaam gingerly held the baby and rocked her in his bony arms.

“You are a natural, Paimaam!” the daughter exclaimed.

“Paimaam, will you play rummy with me?” the mother-in-law asked in a quavering voice, shuffling a pack of cards.

Paimaam dandled the baby on his knee and picked up his cards with one hand. The baby stared fixedly at him for a few moments then a warm jet of pee rose from behind the lop-sided cloth diaper and landed on Paimaam’s trousers.

“Oh, oh, my trousers!” he wailed. And he had only just begun his social calls for the day!

Frightened by Paimaam’s reaction, the baby began to holler. Her mother swooped her up, “The Breast-Feeding Bible says one should nurse whenever the baby is upset,” with this announcement, she rushed into the bedroom. “Myna, our maid, will wash your trousers.”

“I, too, must use the bathroom many times.” The grandmother confided. “It’s the new medicine I am taking for my sugar.” She stopped dealing the cards and tottered unsteadily to the bathroom.

Paimaam hesitantly removed his trousers and handed them to Myna. He was wearing striped, blue cotton shorts underneath. Being an old-fashioned man, he also wore a codpiece below his shorts.

Thus attired, he waited at the dining table.

The doorbell rang.

Paimaam panicked. “Somebody, open the door!”

The doorbell rang stridently, again and again.

“Hey, somebody open the door!” Paimaam cried in anguish.

It could be Mr. Wagh himself, or his good wife. It was no use. He would have to open the door himself.

Anil Kaka stood outside. Anil Kaka glanced at the figure of Paimaam in his blue striped cotton shorts and his mouth fell open.

“Paimaam! What kind of indecent attire is this? And look, the tail of your codpiece is showing.”

“The baby peed on my trousers, and the maid is washing them right now.” Paimaam replied sheepishly.

Anil Kaka entered. He and Paimaam sat in the living room, where the latter waited for Myna to finish drying his trousers by ironing them. He prayed they would be dry before Mrs. Wagh or Mr. Wagh himself arrived.

Anil Kaka eyed him maliciously. He went into the kitchen and returned with a bed sheet that had been drying on one of the drying rods. “Here. This is more decent,” Anil Kaka said.

Paimaam looked quite demure with a bed sheet wound around him like a skirt.

Paimaam and Anil Kaka gazed at each other warily. Paimaam suspected that Anil Kaka cracked jokes at his expense and made fun of him, and this incident would only give him more fodder. Paimaam never made fun of anyone. Anil Kaka was suspicious of why Paimaam hung around high officials. It was different with him. He and the director had been friends since boyhood.

The doorbell rang once again. Myna interrupted the task of drying Paimaam’s trousers to open the door. Mrs. Wagh sailed in.

“So sorry to leave you, Paimaam. Oh, even Anil is here. Well, my husband will be arriving any moment now. Are you sure you won’t join us for lunch, Paimaam?” She tactfully showed no surprise at Paimaam’s attire.

“How is Mami?” She made the customary inquiry about Paimaam’s wife.

“Oh my God!” Paimaam said, thunderstruck. “I forgot that I left her at Khadi Bhavan. I must rush there.” He sprinted into the kitchen, snatched his trousers from the ironing board, and hastily put them on.

Paimaam stumbled out of the Wagh’s chauffeur-driven car on the busy road outside Khadi Bhavan and rushed towards Mami who sat on the pavement weeping. At the sight of her husband—striding on his storklike legs with a wet patch between them, heedless of traffic, arms outstretched, and tears rolling down his wrinkled cheeks—she wept some more.

Ravibala Shenoy lives in a suburb of Chicago. She has published award-winning short stories, flash fiction, CNF, memoir and poetry. Her work has appeared in Chicago Quarterly Review, Best Asian Speculative Fiction, Superstition Review, Bosporus Review of Books, Literary Mama, Funny Pearls, and other online and print publications. She is a former librarian and book reviewer.

Featured photo by Ekam Juneja (Pexels)