Neera Kashyap

Genre: Poetry

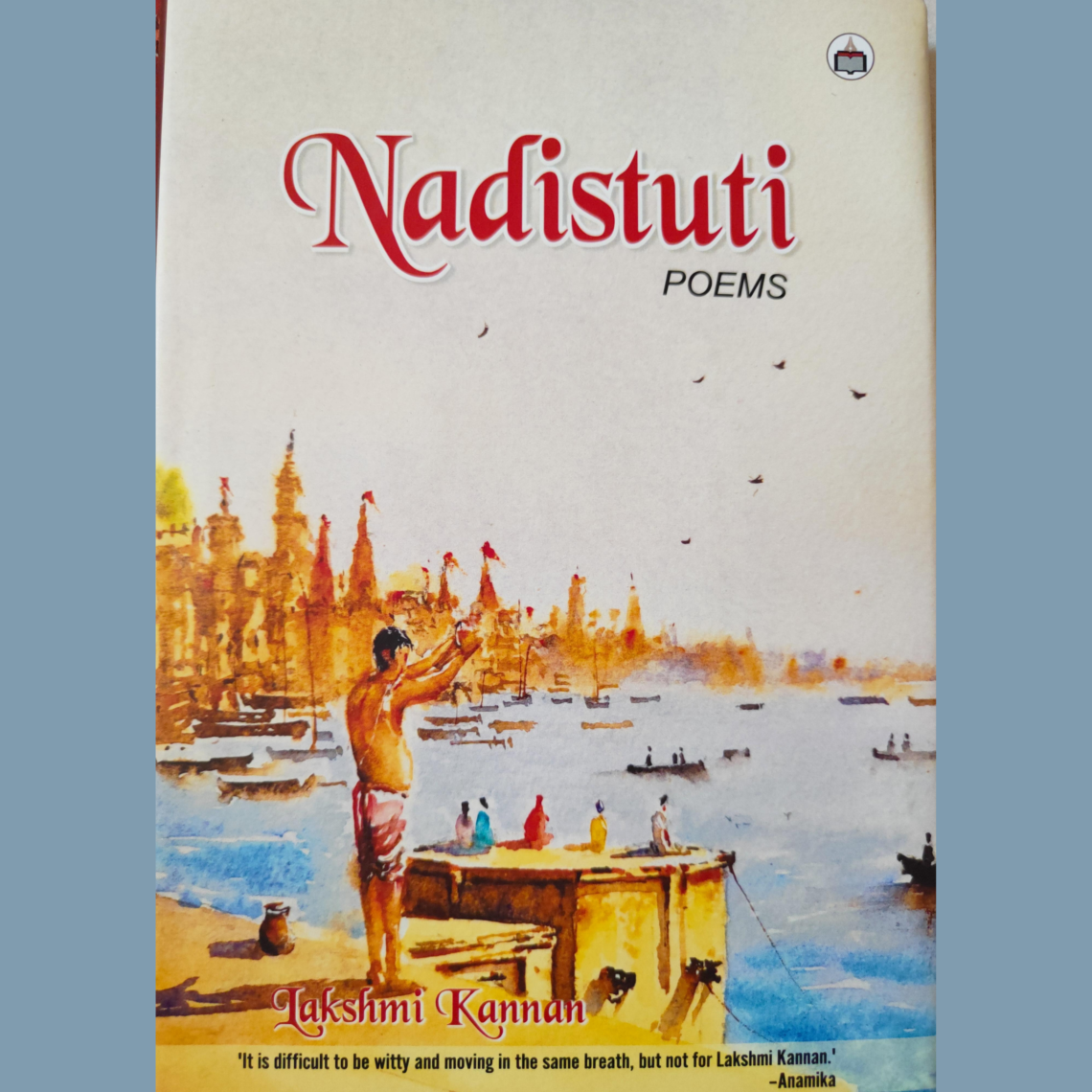

Publisher: Authors Press (2024); ISBN: 978-93-5529-939-0

Price: ₹ 495

Pages: 102

A bilingual novelist, poet, short fiction writer, critic and translator, Dr. Lakshmi Kannan is a distinguished figure in both English and Tamil literature. Nadistuti is her fifth collection of poems in English, her earlier poetry collections including Sipping the Jasmine Moon (2019) and Unquiet Waters, published in the same volume as Ketaki Kushari Dyson’s In That Sense You Touched It (Sahitya Akademi, 2012, 2005).

Divided into five segments, Naman, Nadistuti, Chamundi, Mandala and Fireside, Nadistuti is an interconnected riverine flow of poems that reflect each other in a brilliant kaleidoscope of mirrors that glint of philosophy, history, traditional and religious rituals, feminism, humor, poignancy, tenderness, the personal and a quest for the transcendental. There is a sharp clarity to her poems which is simultaneous with the music of waves as they ebb and flow.

In the very first segment, Naman, we feel the force of a river – stemmed. The poet articulates shock at the suddenness of lives lost due to COVID, lives well known and admired. One such person was H.K. Kaul, who founded The Poetry Society, India, along with other poets including Lakshmi Kannan. In remembrance, Lakshmi prophetically quotes resonant lines from his last book of poems:

Here on the slopes of Shankaracharya

I face Dal Lake at the dusk of an era

Sitting on a slippery stone I try

to balance between the time lost

and the dark night ahead.

With fifteen poems, the second segment, Nadistuti, is the longest in the book. It flows with the strength of rivers, both mighty and seasonal. The very first poem, ‘Narmade’, brings divinity to daily life. It is befitting that before taking a bath, a hymn from the Rig Veda is chanted to invoke the holy rivers Narmada, Sindhu, Kaveri, Godavari, Sarasvati, Ganga and Yamuna to divinize the bath waters and make them pure. Spiked with delicious humor, in the poem ‘Nadistuti’, the bather must quickly recite the shlokas, allowing the seven rivers to splash around his head before the municipal tap lets off a guttural cough to run raucously dry!

There is a poignant humility in the reminder that even a mighty river such as the Kaveri has its origins in a small stream with a tiny shrine, Brahma Kundikai. It is in a long prose poem, ‘Ponni looks back,’ that we discover, again with poignancy, the historicity and grand sweep of the Kaveri, affectionately referred to as Ponni, as she courses on with dynamic tempo, nourishing the soil of two states through 475 miles: “An expansive, primordial, mnemonic, deathless mother to one and all.” She sees herself as witness to the era of the full-bodied Chola sculptures, the austerity of the Pallava art, the ritual worship of women and children in her waters through generations, the festivals and baths for ritual healing. The course changes. Kannan brings this flow to an abrupt turn with “different voices floating over my waters … the Kaveri dispute, wrenching my waters apart” (‘Ponni looks back’). In her final mergence in the Bay of Bengal, the river wishes to forget: “But so long as I flow, I am their time and I will see and remember even the painful things” (‘Ponni looks back’).

The use of mythology makes rivers come alive in timeless ways. In ‘Blue God,’ Krishna is forever entwined in the waters of the Yamuna, vanquished as he did Naga Kaliya who inhabited her waters; frolicked as Krishna did on Yamuna’s banks with Radha “in a love that defied marital bonds.” In ‘Sarasvati’, the invisible river flows quietly, unobtrusively underground, to form the Triveni Sangam with the Ganga and Yamuna at Prayagraj, a tangible goddess who flows on through the very bloodstream of the devotees she inspires.

The underpinnings of feminism reveal themselves in the poem ‘High and dry.’ The river Gomti can be “a grimy stain or the thin stream in the far corner … quiet and acquiescent …. left high and dry.” But every few years, she swells and rises in fury:

It’s when you menace buildings,

gobble up boats, cattle, huts,

or a whole village and ask for more,

that’s when the entire city wakes up to you. (‘High and dry’)

It’s in the personal that Kannan truly scores. In ‘Aarti’, with prayerful symbolism, she lowers her sons into leaf boats, complete with sacred leaves, flowers and oil wicks, onto the flowing waters of the Ganges. She watches them float away and become indistinguishable from other leaf boats in a classic image of detachment. In ‘Visarjan’, she wonders how the formidable Lord Ganapati goes down so easily in the waters, “sending up afloat / a few flowers and kusa grass, / his parting gifts,” whereas “I’ve dived in and out / of the same river, / my body unmelting, / stubbornly solid.” She ends with the questing question:

Would I ever learn

from him to dissolve, to mix

the earth of my being

with the waters? (‘Visarjan’)

Like the river Gomti in full spate, it is in the section Chamundi that Kannan flows with feminist fervor. In ‘Anger becomes her,’ while one daughter is docile, the other prefers cathartic anger “to cleanse sinful subterfuges / to fight gropers, predators, infantilizing wolves / within her home, and outside.” Intertwining mythology with contemporary times, ‘Chamundi Hills’ sees Mahishasura discard his armor of sword and cobra to don denims, classy sharp suits, trendy glares and polished shoes along with blameless behavior. But his conman guise can be seen through: “Those who glimpsed the asura / through the refined veneer / became Chamundis / their eternal guruma.”

Kannan’s riverine music flows through her feminism. In a family mansion and poem named ‘Hemavati’, “the boys morphed into bums / the girls were profluent, gurgling onward.” The girls flow out symbolically in search of their mother, river Kaveri, reminiscent of the river Ponni who has blessed them as infants in her waters, now enfolding them as women in her embrace. In a deep and intriguing poem ‘Snake Woman,’ which describes elaborate rituals that accompany worship of snake sculptures on temple walls in the hope of conceiving a male progeny, there is also a secret but persistent nocturnal dream that points to a different outcome: “a female baby cobra appeared / wearing jhumkies and a jewelled girdle / around its slender neck, / a red dot shining on its brow.” Through this powerful poem, Kannan strikes at fertility rites and societal son-preference, and the potency of dreams as possible portents of reality.

The segment Mandala has both the beauty and ephemerality of a Buddhist mandala – a symbolic picture of the universe meditatively created and then dismantled, symbolizing the beauty, impermanence and renewal of life. In ‘Kolam’ women create elaborate patterns with rice powder on mud-swept front yards, only to wash them away to make, unmake and re-make mystic designs around renewable dots. In ‘14 April, 2020,’ the creamy neem flowers that inevitably rang in the Tamil New Year, yielding a special neem rasam made with its bitter flowers, tamarind and jaggery, no longer do so. Now, on this assured date, the buds remain closed while all other seasonal flowers bloom around the neem in all their glory. ‘Dream Book’ brings in the personal so uncannily that a dream hints even to the reader to drop karmic baggage and travel free. It’s the blessings that feel durable even when, as in ‘Jiva and Isvara,’ the Upanishadic references are to two birds – one that digs deeply into the luscious fig of life while the other feels “completely satiated / by the fruit he never ate.” For the poem ‘Picchai’ movingly presages the next personal segment through a note of gratitude for all the blessings received: food, a clean family life, a green environment, books, mentors, gurus, friends.

I had only asked, with my palms folded,

bhavathi bhikshaam dehi.

The picchai you gave spills over. (‘Picchai’)

It’s the final segment, Fireside, that is profoundly tender, and to some extent, self-revelatory, dealing as it does with relationships in the family. Here the river Kaveri flows again as Kannan’s Tamil pen name chosen for her by her husband, “flowing in her ink” (‘Kaveri’). It is from her famous artist mother that she learns to listen to a blank canvas and to what it will yield. For Kannan it is a blank page: “The stillness of the space/sharpens the sounds I begin to hear” (‘A Dialogue’). In ‘Lost and Found,’ her mother collects for her daughter the things she had lost as a girl, poignantly revealing in three sharp lines the weight of her own lost childhood: “‘This box contains your childhood years,’ she said / and a bit of my childhood too I lost / when I got married at eleven.”

In ‘A room of one’s own,’ the poem reveals how Kannan as a mother perceives her son and his presence: “For I know he is there, like a motherly father, / a young friend, or a fierce fighter / his protean personas tucked into the son.” And for her daughter-in-law’s love and care, she offers a huge bunch of yellow roses: “She smiled / and buried her face in them. / They spoke to her softly” (‘Yellow Roses’).

Perhaps it is befitting to end this review with the last verse of Kannan’s end poem, ‘If you want to visit.’ After a host of images that connote a wholesome family life gathering around the living room like homing birds, with the voices of friends on phone being warm and close too, Kannan writes:

Come,

Visit me now.

I’ll not have a word of complaint

I’ll gather all of these and leave with you. (‘If you want to visit’)

Nadistuti: poems can be purchased here.

Neera Kashyap is a writer of short fiction, poetry, essays and book reviews whose work has appeared in several international literary journals and anthologies. Her collection of short fiction is in the pipeline with Niyogi Books. She also hopes to bring out a collection of poems in the near future. Her essays and book/theatre/film reviews have appeared in Mountain Path, The Chakkar, Café Dissensus, Bangalore Review, Kitaab, RIC Journal & Countercurrents. X: @Neerak7 IG: @neerakashyap FB: Neera Kashyap

Featured photo by Neera Kashyap