Matthew Johnson

I will never be convinced that sports are not a high artistic and creative pursuit like say, music, drama, visual art, or literature. I have found as much creativity in watching Peyton Manning orchestrate a two-minute drill as I have seen actresses like Lucille Ball or Julia Louis-Dreyfus lighting up the small screen with scene-stealing shenanigans.

As a former sports journalist, an ongoing sports enthusiast, and a creative writer who occasionally writes about it, I know sports as a medium has taken body shots like an ignorant fighter who just won’t go down.

I’ve heard plenty of disparagement, that sports are nothing more than circles and bread, a trivial spectacle that diverts attention from the supposed profound and meaningful pursuits of intellectual and artistic endeavors. That the passion surrounding games and athletic achievements represents a shallow fixation on physical prowess rather than philosophical and cultural depths that could allegedly be put to better pursuits. That many fans, with their excessive aggression, overblown sense of entitlement regarding their favorite teams and athletes, and disregard for sportsmanship, respect, and empathy ferment a space of toxicity that rivals an environmental disaster.

Well, that last part is true.

As someone who studied to enter the industry of sports journalism and media and worked in it for a few years as a journalist and editor, I’ve read brilliant reporters and writers like Wright Thompson and William C. Rhoden as I was honing my craft. These are writers, as well as others like Sally Jenkins and Dave Zirin, who have confronted and challenged how I not only look at sports as a writer and fan, but at identity, immersive storytelling, and the human condition.

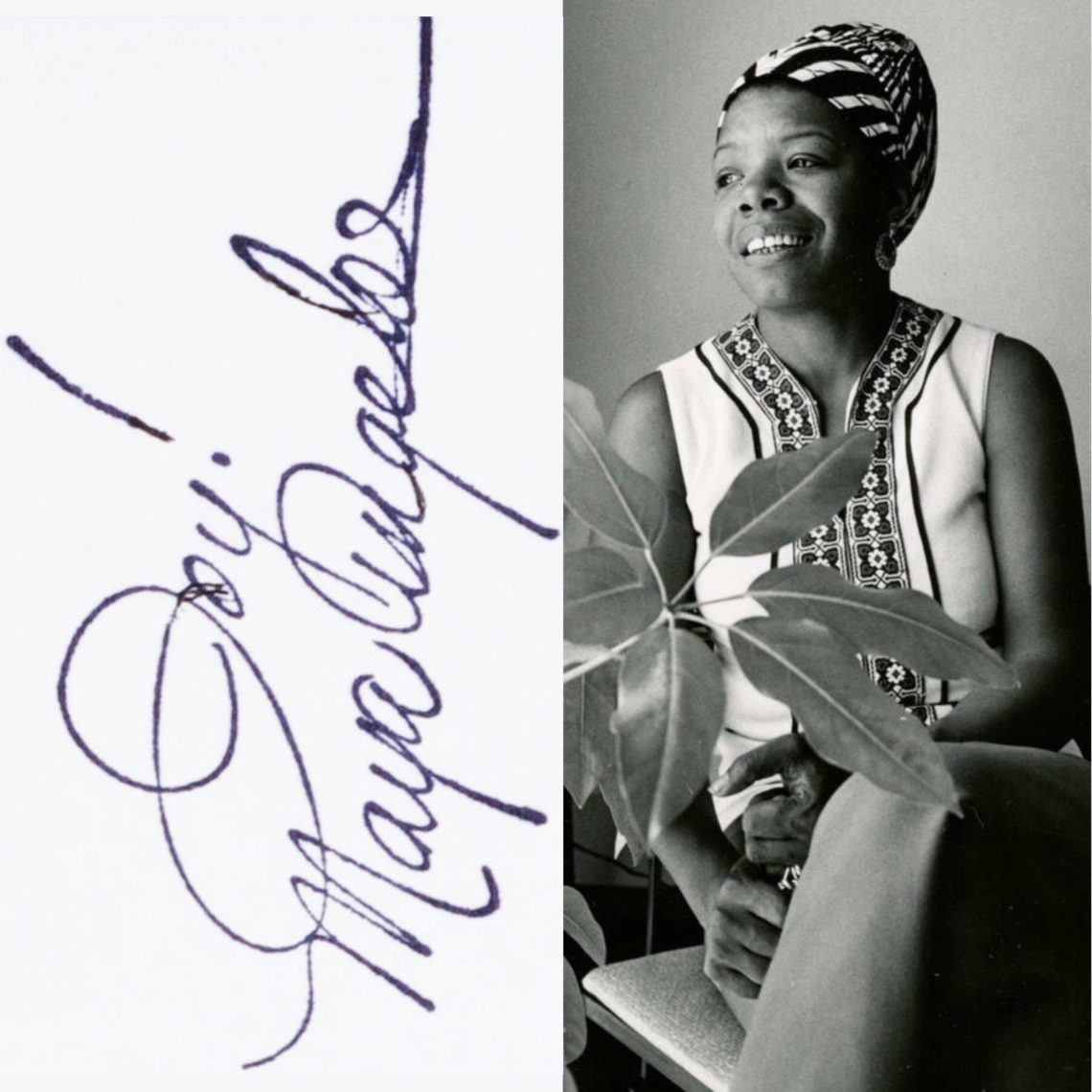

And yet, in my nearly two decades of reading countless essays, columns, books, and creative pieces about sports, when it comes to captivating prose in the world of athletics, the piece that I am continually drawn back to was not written by a daily sports reporter. It was written by the Renaissance woman herself, Maya Angelou, whose “Champion of the World,” reigns supreme, outshining all others for me, in the genre of sports writing.

In this chapter in her biography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Angelou takes readers to Stamps, Arkansas, where her family and many of the neighbors in her community came together in the same space to listen to the great Joe Louis defeat Primo Carera in a heavyweight boxing match on the radio.

In the history of American sports, if there is any athlete who deserves to be highlighted with expressions of praise, that would be the great Joe Louis, arguably the greatest boxer (which is a sport that goes back to antiquity). An influence on future fighters like Rocky Marciano and Muhammad Ali, Louis’ tremendous legacy inside the ring was only surpassed by what he represented outside of it. In contrast to Jack Johnson before him and Ali after him, who were each bold and brash fighters who unsettled white audiences with their outspokenness, Louis navigated the segregated atmosphere of his time as a popular figure in White America.

In response to someone describing Louis as a “credit to his race,” implying that there were diminished expectations for Louis due to being African American, famed sportswriter Jimmy Cannon gave the retort, “he is a credit to his race, the human race.”

Louis was an ambassador and advocate for civil rights, however, while his knockout punches shattered opponents, his more reserved poise and sportsmanship soothed white audiences, allowing them to cheer for him while grappling with their own biases. The defining moment of this sentiment, and arguably his career, was his defeat of the German fighter, Max Schmeling, as World War II loomed on the horizon, and the two men in the ring came to represent competing nations in a global drama.

And yet, despite being, at one point, the most famous and beloved athlete in the country, in, “Champion of the World,” Angelou goes beyond simply capturing Louis’ greatness as a fighter. A brilliant writer, she embraces the challenge of crafting a narrative that’s rich with a personal voice, layered with emotions, and filled with vibrant energy, as if she was watching the fight from Yankee Stadium itself. By doing so, Angelou is not just telling the play-by-play of an ordinary sporting event; she invites her readers to experience it.

Another sports writer I have admired is Dan LeBatard, formerly a regular columnist for The Miami Herald, and I am not sure if he’s the one who created the phrase, but I have often heard it from him, that, “sports are the funhouse mirror to society,” which is a method Angelou uses to heighten suspense and to bridge the gap between topic and reader if they are not a follower of boxing.

As an African American athlete, Louis’ success challenged the prevailing racial stereotypes of the era. Louis became a symbol of pride for many in the Black community, showcasing that excellence in sports could transcend racial boundaries. His victories were celebrated not just as personal triumphs, but as collective achievements for African Americans, so when he struggled in the ring, it felt like a collective struggle to the black community.

As Angelou eloquently writes about her champion, Louis, at one point struggling in the fight, she described the feeling as: “My race groaned. It was our people falling. It was another lynching, yet another Black man hanging on a tree. One more woman ambushed and raped. A Black boy whipped and maimed. It was hounds on the trail of a man running through slimy swamps. … If Joe lost we were back in slavery and beyond help.”

When I personally write about sports, especially creatively, it can be tempting to rely on simple proclamations: “Player X is great, and here’s why.” But, that’s akin to painting a portrait using only one color.

As with any form of artistic creativity, the creator should be adding something unique to the medium. Through Angelou’s lens, the match is more than just a contest of strength which could be found in any sports section in a newspaper; it is a mirror reflecting the struggles and aspirations of an entire people. Her words resonate with the weight of collective history, as each choice in her language is filled with the tension and triumph of not just the moment, but of a people.

Moreover, Angelou’s exploration of the social and emotional ramifications of the fight provides a rich, textured backdrop that elevates the story from a simple sports article to a profound commentary on the black experience. She illuminates the struggle of an entire community, rendering their collective exultation in the face of Louis’ struggle and eventual victory with such depth and grace, that it transcends the bounds of the boxing ring:

“Champion of the world. A Black boy. Some Black mother’s son. He was the strongest man in the world,” wrote Angelou. “People drank Coca-Colas like ambrosia and ate candy bars like Christmas. Some of the men went behind the Store and poured white lightning in their soft-drink bottles, and a few of the bigger boys followed them. Those who were not chased away came back blowing their breath in front of themselves like proud smokers.”

Perhaps because they were two of the first professional sports that fixated the country, and remain popular to this very day, countless creative works have been produced through the prism of boxing and baseball. From canonical writers of an undergraduate literary class, like Ernest Hemingway and Mark Twain, to modern contemporaries like Joe Posnaski and Joyce Carol Oates, there are a lot of ways to get romantic about baseball or to chronicle the brutal ballet that is boxing.

When I review poetry submissions for the literary publication I am a staff member of, The Twin Bill, a baseball-themed magazine, the pieces that often get selected for publication are not play-by-play rundowns of a diving outfielder or a middle-relief pitcher winding up to hurl a curveball. Poems such as “Spitballing in the Writing Center” by Tim Peeler and “The Meaning of Life According to a Groundskeeper” by Ethan Altshul look at life through baseball from a unique perspective. The subject matter of these poems is baseball, but the purpose and meaning go beyond the game and would be appreciated by readers of not just the national pastime, but of good literature.

That aim is something I strive for in my personal writing, and while Maya Angelou is not the one who taught me this methodology in writing, her essay, “Champion of the World,” best illustrates that impact.

As Angelou demonstrates in her piece, sticking out with your own voice is not just a choice; it’s a necessary declaration. It’s saying that while the gloves may be standard and the diamond may be uniform, your interpretation of these moments is entirely your own. It’s about daring to be different, to embrace your quirks, your insights, and your voice.

Matthew Johnson is the author of the chapbook, Too Short to Box with God (Finishing Line Press) and the poetry collections, Shadow Folks and Soul Songs (Kelsay Books) and Far from New York State (NYQ Press). His work appears in The London Magazine and Roanoke Review. A BoTN and Pushcart Prize nominee, he’s the managing editor of The Portrait of New England and poetry editor of The Twin Bill. www.matthewjohnsonpoetry.com

Featured Photos: (Left) Signature of Maya Angelou on a typewritten copy of her poem “Caged Bird” (1983) auctioned at the 2013 edition of Doodle for Hunger; (Right) Portrait photograph of Maya Angelou by Jill Krementz, March 25, 1974. Both photos are in the public domain and have been obtained from Wikimedia Commons.