The true value of reading the novels great writers never managed to finish

Shane Schick

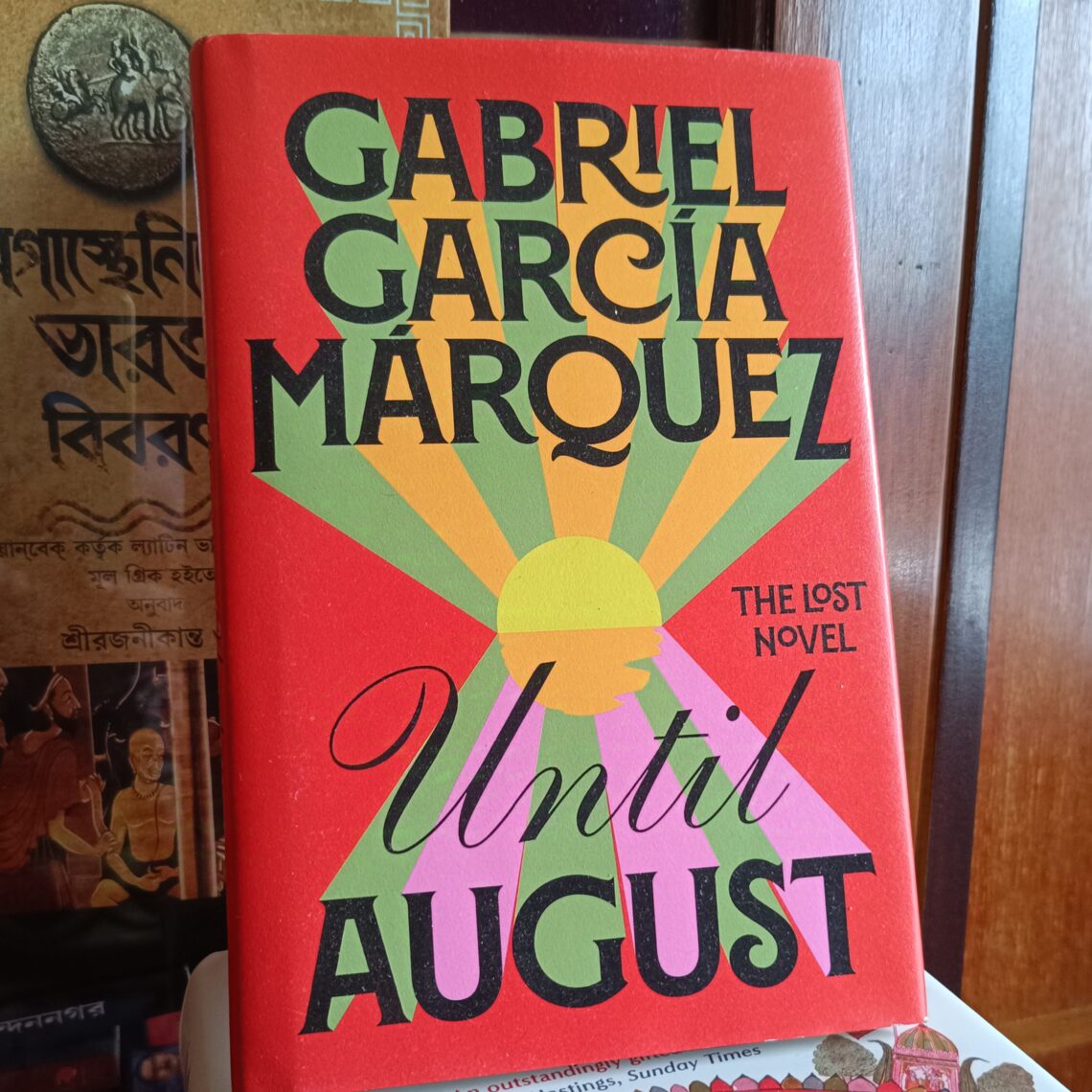

When Garbiel Garcia Marquez’s final novel, Until August, was published posthumously earlier this year, the New York Times was quick to dismiss it as “an unsatisfactory goodbye.” Kirkus was kinder, describing it as “not bad, but far from Gabo at his best,” and the Guardian called it “slight.”

The only thing we can be sure of is that it did not turn out as he intended.

Discovered shortly after Garcia Marquez’s death a decade earlier, Until August (En Agosto Nos Vemos in the original Spanish) spans roughly 150 pages. This is far shorter than One Hundred Years of Solitude, or even The General In His Labyrinth. While it contains five sections centered around a character named Ana Magdalena Bach, it was never completed.

As such, Garcia Marquez’s book will join that singular pantheon of novels that, at their best, serve as a tantalizing coda to the rest of the work they produced. Sometimes they represent genuine publishing events. More often, they are assessed based on what was left missing. Rarely are they ever associated with one another. Yet they often produce a strange and unique enchantment all their own.

I am hardly the first person to find myself unusually attracted to literary summits that haven’t been fully scaled. Grant Shreve’s 2018 essay for The Millions, ‘In Praise of Unfinished Novels,’ considers the case of Ralph Ellison’s never-completed second novel, Dicken’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Jane Austen’s Sandition and other examples of work that still had several chapters to go. Shreve wondered “if unfinished novels constituted a genre of their own and, assuming they did, whether it would be possible to assemble a canon of literary catastrophes.”

The answer, I think, is that they don’t make up a genre, if we take that to mean categories of novels with similar plots, themes, situations and characters. And they’re not necessarily catastrophes, either, because there’s no guarantee that a completed version would have met the expectations of either author or readers.

Instead, unfinished novels may be more like a literary form – an accidental one, perhaps, but with some recognizable characteristics. As Shreve pointed out, these novels “demand that we attend to dead ends as well as to false starts, to charged silences as well as to verbal excesses. They ask us to see what meanings can be gleaned from a process that has not yet hardened into product.”

That said, assembling a canon may not be what we need, especially since there are already plenty of listicles online that try to do that already. More useful would be to identify the criteria for assessing such novels – to distinguish which are worthy of attention, and which are mere remnants.

The first, almost conditional quality is that the author has already published work of literary significance. This could be limited to a single novel, but it’s hard to imagine much interest in an unfinished novel by an author who was otherwise unpublished (Kafka, who had a few stories appear before his death but whose novels were all in various states of incompletion, is the exception that makes this rule).

The overall creative achievements of an author are important because their unfinished novels tend to be read in relation to them, rather than in situ. In other words, the reader of Hemingway’s The Garden of Eden inevitably weighs its qualities against The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms and For Whom The Bell Tolls. To what extent does such a novel reflect the author’s strengths? What does it suggest about the maturing of their style, or new directions in which they hoped to head off? Considering these sorts of questions – even if no definitive answers can be found – is part of the value unfinished novels offer.

A second hallmark of the best unfinished novels is the way they capture the ambitions, and even the obsessions, that marked their author, or which evolved naturally from their work and life. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon (sometimes titled The Love of the Last Tycoon) is a good example. It makes a perfect kind of sense that the author who pierced through the illusory glamour of the 1920s in The Great Gatsby would explore the (still young) world of movie studios that were beginning to manufacture glamour for mass audiences.

The same is true for Truman Capote. An author who swanned his way through high society, Capote had always understood there was a darker side, an understanding he brought to life in works like Breakfast At Tiffany’s. Having confronted the worst in humanity while writing In Cold Blood, however, he was ready to go further with Answered Prayers. The unfinished novel took its title from St. Teresa of Avila, who wrote that “[t]here are more tears shed over answered prayers than over unanswered prayers.” Capote may have scored a triumph with In Cold Blood and his black-and-white ball, but disappointments persisted, providing readers who even have a high-level knowledge of his biography a critical backdrop when they open Answered Prayers for the first time.

Then there’s David Foster Wallace, who dared in The Pale King to attempt the great American novel about boredom. For the author of A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, there is a feeling that The Pale King is a sort of culminating activity in the subjects he never tired of studying.

Unfinished novels also resonate more deeply when they not only build upon what the author has previously written about, but bring us closer to who they were. These late works tend to be more personal, and the circumstances of their deaths can create an unintentional emotional undercurrent to what they left behind. The First Man, which Albert Camus never completed, was based upon his childhood in Algeria, a bildungsroman-in-progress that may fixate the reader in part because it was cut short by Camus’s death in a 1960 car crash. This gives the novel a poignancy in its effort to make the author of The Stranger . . . less of a stranger.

The ultimate test of an unfinished novel, however, is the extent to which it invites readers to imagine how the author might have gotten it to the finish line. This is connected to the thing great literature always does: through descriptions, dialogue and other tools, our favorite authors help us to imagine what other people, and entire worlds, look like. Our imaginations fill in the blanks better than the best films and TV shows manage to do.

An unfinished novel takes that collaboration between writer and reader to a new height, where we can begin to conceive of a final half, an ending or simply refinements that would have been made to the manuscript as a whole. Even structure can be up for grabs: Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, which was written on various scraps of paper, wasn’t left with a specified order. Publishers have had to make the decision of which sections should follow one another – decisions which readers can question and challenge as they read.

It’s possible that the gratification of reading unfinished novels will not always be confined to what is published posthumously. I love the way, in his onstage and video interviews, the curator and critic Hans Ulrich Obrist always asks artists, “Do you have any unrealized projects?” They almost always do, and the projects they describe often provide a tantalizing glimpse into the creative mind and the nobility of certain so-called failures. We should start asking our contemporary authors the same question, and possibly even encourage them to share them. This is already being done at the idea stage: Édouard Levé’s Works, for instance, is an imaginary list of more than 500 unwritten books. George Steiner’s My Unwritten Books goes into even greater detail about the prospective tomes he never turned in.

In the meantime, we can wait and wonder. Maybe the long-rumoured follow-ups to J.D. Salinger’s Glass family stories will one day be released from his safe. Perhaps there are works still in draft form from recently deceased literary greats like Milan Kundera, Martin Amis or even Cormac McCarthy. As Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s book proves, the history of unfinished novels is just getting started.

An older version of this piece originally appeared in Issue 3 of The Hooghly Review.

Shane Schick has had poems published in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., India and Africa. He lives with his wife and three children in Whitby, Ont. More: ShaneSchick.com/Poetry. X: @ShaneSchick

Featured photo by Tejaswinee Roychowdhury